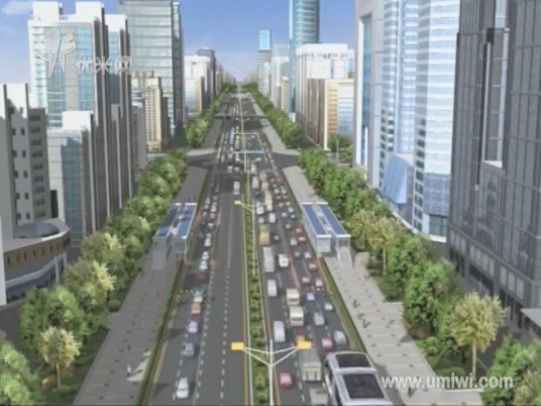

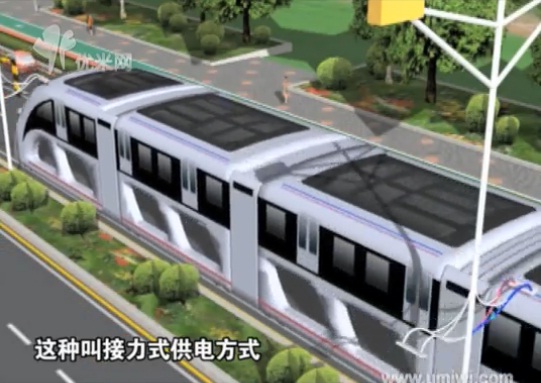

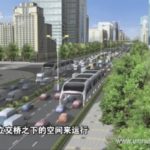

A couple of days ago, chinahush.com posted a video (in Chinese, English translation included) showcasing the concept of a bus running above traffic. The idea is that the bus is basically a moving tunnel, with a 2 meter clearance below for normal car traffic to drive under. Thus the bus can drive above traffic without being stopped by traffic jams or without stopping traffic when it is itself stopping at a station. At the same time, the bus still fits under overpasses. The buses are four carts long, each cart taking up to 300 passengers, and are supposed to go up to 60 km/h.

This seemingly solves to problem of creating right of ways for public transportation. Subways have their own right of way, unimpeded by any other traffic, and not interfering with anything else. But they are also the most expensive. Elevated tracks also represent a dedicated right of way, but they might disturb the cityscape, due to noise and darkness below, and will only fit along certain streets where they still may take away some space due to heavy construction. Buses usually don’t have their own right of way, except for bus rapid transit. So buses may get stuck in traffic and also may – from the point of view of drivers – create more traffic. Of course a bus may replace a large number of cars. On the other hand subways are the most expensive, while buses are the cheapest (at least in terms of initial construction). So the “straddling bus” may give both advantages, of creating it’s own right of way but not disrupting traffic, by simply bringing it’s elevation structure along with itself — basically, it is its own overpass. The claim is that the cost is about 10% of what a subway would cost.

Dario Hidalgo over at The City Fix brings home the point that this concept might not actually solve any real issues:

The plan is really innovative, but seems to be at a very preliminary concept stage with too many issues to solve from the engineering standpoint. For the time being, it would be much better to dedicate time and effort to simpler and more effective transit solutions, rather than making concepts that preserve space for cars.

Another issue is that to make this system work, one may have to make some compromises which will actually make this system inferior to already existing systems like bus rapid transit or light rails, although some of the ideas could maybe be reused here.

Any information besides the video, which may very well come from a TV show where the audience has to guess whether presentations are fake or not, is hard to come by. Let’s just assume this idea is for real and will actually be implemented. And since I like innovative transit concepts, I decided to take a closer look, and at some of the issues that come up.

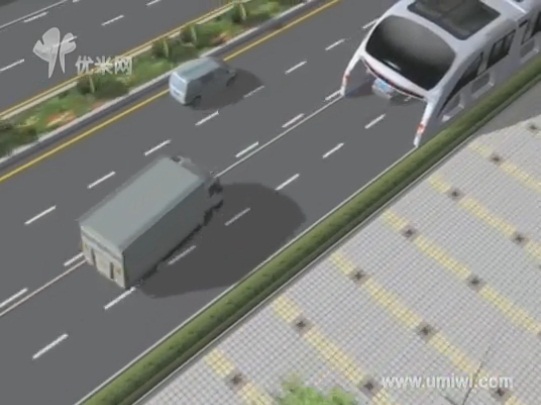

keeping away trucks

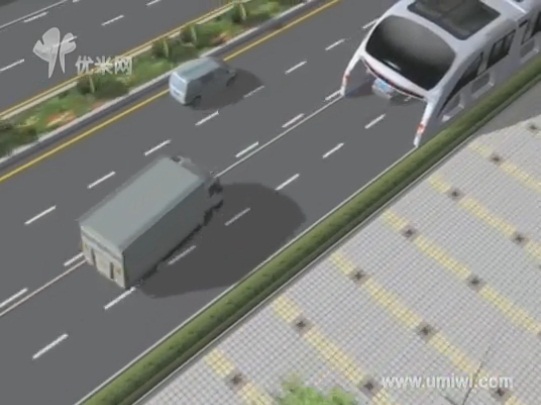

The clearance below the bus is planned to be 2m, which means that trucks will not fit under it. Some of the images show this bar construction presumably to keep trucks away. It seems to me that this is not enough to keep trucks actually separated from these lanes. There are already problems with drivers who are not aware of low clearances and drive into these areas. It would seem that a more solid approach would be more appropriate.

At other points in the presentation it actually shows trucks driving on the same lane as the bus. Some sensor system in the bus would detect that the truck is too high, and will warn trucks to change lanes to avoid a collision. This is an even more dangerous approach. Drivers now have to be even more aware of low clearances ahead — of another moving vehicle — and then react to some small display at the rear of the bus telling it to switch lanes, which might not always be easy. Another issue is that the bus might be driving up to a truck which is stuck in traffic ahead of it.

Even if drivers were vigilant enough, it would mean that the bus cannot really drive much faster than the slow moving traffic for safety reasons — and if the cars are stuck, and there is a truck among them, then the bus will be held up as well. It would probably be best to completely separate all tall vehicles away from any lanes where the bus can go, and make sure of that with barriers that cars have to drive through before turning onto the bus lanes.

This would mean that there would exist a secondary grid where only cars can go, which might be quite a hindrance for any traffic of large vehicles. Even on a four lane boulevard where only half of them will be low clearance, it will create problems for large vehicles to turn left or right (depending on whether the bus lanes are the inner or outer ones). This is somewhat ironic — usually trucks delivering goods or other high occupancy vehicles are the ones that should get somewhat of a priority, but this scheme completely seems to prioritize individual car transport. And if there are only two lanes to begin with, like in the picture on the side, then any large vehicles can’t go there at all. I wonder whether just dedicating one lane to either BRT or a light rail would create less of an impact on other motorized vehicles.

avoiding collisions

Even if trucks could be reliably kept away, there is still the issue of avoiding collisions. Imagine driving on a highway in heavy traffic, and having this thing whoosh over your head. The presentation shows that sensors in the bus would detect vehicles that get too close and warn them with lights and sounds. This will create a very disorienting situation with all sorts of conflicting visual information from all sides and little visibility of the fixed environment. And if there is an accident, hitting the bus from the inside, it is quite possible that a lot of people might get hurt. It would probably be better to create railings behind which the bus drives, to minimize the chance of bad accidents. It would also ensure that no vehicle crosses from a bus lane to a non bus lane as the bus approaches from behind, which will slow the bus for sure, if it doesn’t cause an accident. Again this will increase the amount of space needed for the whole contraption, meaning that one could just dedicate a single lane for a more proven form of transit.

tires vs tracks

From the presentation it is not very clear whether the vehicle is running on rubber tires like the name ‘bus’ suggests, or running on tracks like a streetcar. Besides the problems of staying exactly on track, having such large and heavy vehicles go along the exact same path on the road presents some problems. Bombardier experimented with a streetcar bus hybrid, called Guided Light Transit. It’s basically a streetcar vehicle running on tires, guided by a center rail. The idea is that it can operate like a streetcar in downtown, but does not need the rail along it’s whole path, giving it more independence and flexibility over a regular tram. The hope was that this system would be cheaper. But one of the problems is that due to the heavy vehicle always riding over the same spot, the asphalt deteriorates much quicker. Adding to that the added maintenance requirements of rubber tired vehicles, and the system actually turned out to be more expensive than a regular tram. The Bombardier vehicle only weighed about 40 tons, while the straddling bus should be much heavier. Thus rails would really seem to be the only option to ensure that the bus is properly guided and the maintenance is manageable.

stairs

Having stairs inside a transit vehicle at first sight seems like a good idea. Due to the wide width of the bus, one can easily fit stairs inside it while still leaving space on the sides to pass. This would allow entering through and exiting to (existing?) overpasses, and would reduce the amount of engineering required to build stations. One would merely need pedestrian overpasses that are required over very busy roads anyway, and no actual platforms where the bus would have to stop.

The main problem is that entering and exiting through stairs will hugely increase dwell times. In usual rapid transit, passengers enter and exit through many doors and level boarding will make sure that the time required to get everybody out and in is fairly small, in the range of a few seconds. Decreasing the number of steps required reduces the boarding time, that’s why low-floor buses and streetcars are becoming the standard. Level boarding is also one of the ways Bus Rapid Transit achieves high throughput. Instead of requiring a few steps, the image shows a full flight of stairs. This does not only impede accessibility, but also increases dwell times to the point where the overall average speed of the bus will hardly compete with normal street running buses.

Probably to increase throughput, the presentation proposes this oval shaped overpass, which appears to allow two sets of stairs. Not only will this reduce the capacity inside the vehicle, but it will also mean that the amount of engineering required will not be much different than having an island platform below a simple overpass – thus it makes the case for stairs moot.

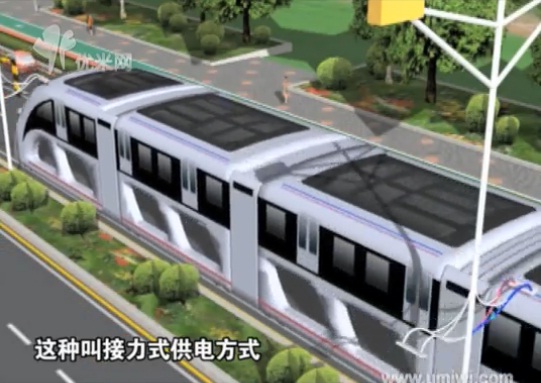

power transmission

One interesting aspect of the straddling bus concept is the way electricity is to be transferred to the vehicle. As opposed to having an overhead wire and a pantograph attached to the vehicle, the proposal is to use fixed pantographs and a conducting rail on the roof of the car. The distance between two charging poles is smaller than the length of the vehicle, so that it will always get charged. This seems like an interesting idea, and I would like to know the cost of such a system compared to using good old overhead wires.

Another mentioned idea is to use supercapacitors and only charge between stations, making the 3d bus an actual capabus. Super capacitors have a low energy density compared to lithium ion batteries, but allow to be charged much quicker. This it is possible to charge an electric bus at every stop, so that overhead wiring is only used at stations. This idea is not new, and already Shanghai has some capabusses running since 2006.